Wheel & Tire Tech Notes

#1

Tech Contributor

Thread Starter

A number of years ago, when we were racing Porsches, we were asked to develop a series of seminars, to be held at various tracks, on the subject of prepping street cars for racing. Within Porsche Club of America national, there existed a fairly rigorous and effective training program for bringing drivers through “driver education” events, and promoting them to licensed racers. What was missing, however, was a clear and accurate syllabus for CAR preparation.

So, the drivers would become increasingly proficient, but their essentially “street” cars would lag sadly behind. Once they got sick of over-driving their prized Porsche’s potential, they would blindly spend a ton of money, throwing random mods at the car, in the vain hope that it would allow them to go faster. Those who did not pay experienced prep shops to fix their problems would eventually quit out of sheer frustration.

The thought behind our graduated-level seminars was to provide some SIMPLE, ACCURATE guidance to taking a street car, and developing it into a racecar. One of our over-arching criteria was to make the best use of available dollars and time - sort of like a “101 Projects for the Racer”. The end goal was to equip the individual with technically sound methods for evaluating options, and making smart decisions. This may be useful, judging by the never-ending string of threads asking, “What is the best track tire?”; or “ Are 18” wheels better than 17” ?” Next to the motor, wheels and tires are the life-blood of racing!

Where to begin? About four years ago, I was asked to post up a synopsis of our wheel and tire findings (along with other suspension components) on one of the popular Porsche forums. What follows is an abbreviated version of that post. It is quite basic, but should provide a handy spring-board for discussing more advanced aspects in much more detail. So, without further comment . . . . .

I start by making the assertion that there is more to be gained by the proper selection of tires and their wheels, than by ALL of the other suspension components combined.

Also, the comments apply to RACING APPLICATIONS and autocross, focused on racecars, or street cars which are BECOMING racecars.

I include my usual disclaimer about attempting to keep a fairly complex subject AS SIMPLE AS POSSIBLE while covering it thoroughly still applies. To that end, we write in broad concepts, employ metaphors that may not apply in every single case, use plain language, and invoke a minimum of math. (With due apologies in advance to the most experienced racers, other race engineers, and knit-pickers.)

In past posts, we have maintained that “the racecar suspension attempts to manage the chaotic interaction between the race track and the racecar itself - the goal being to keep all 4 tires firmly planted on the track all the time.” So here we start with something as “simple” as tires.

Stating the obvious, there are tires for the street, tires for the track, and then several which attempt to serve “double duty”. Generally speaking, the strictly street tires are not a consideration for the track. The “double duty” tires might be appropriate for the rain if their tread pattern scavenges water effectively. Our focus will be on tires specifically designed for the track.

Following are the primary PHYSICAL characteristics for which we look in a race tire:

1. It has a large footprint (contact patch) for its overall size.

2. Once the release mold has been scrubbed off, the rubber compound is fairly soft to the touch - maybe like a pencil eraser.

3. The sidewall is low-profile and very stiff.

4. Its tread surface which will contact the track is relatively wide.

5. If there are groves in the tread surface, they are few, and very shallow.

6. Light weight.

7. Beads are super-rigid.

8. All tires of the same compound have a common grip level.

The obvious goals here are to get as much sticky rubber in touch with the track as possible, and keep it there. And this leads me to LoPresti’s TireRule #1: If slicks are allowed in your racing class, do not even think about anything else. Your work now becomes determining which manufacture, size, and compound work best with your suspension.

(I have come to realize that NASA employs a conversion factor, or equalization penalty, for using slicks, and here careful testing will be the only way to determine if good slicks can overcome their additional weight assessment.)

A word about COMPOUNDS: The term comes from the notion that the “rubber” in any given tire is made up from a combination of several different “rubber materials” - it is a compound formulation. In racing circles, the term usually refers to how soft or hard the body of the “rubber material”, and how grippy that particular combination. Generally, a soft compound is very sticky, wears fairly quickly, and is designated with a low numerical value. At the other end of the spectrum, a hard compound does not provide as much grip, lasts much longer, and bears a higher numerical value.

If your class limits you to “DOT Approved”, then you have a different range of choices, and the cost-vs-wear factors come into play. Typically, manufacturers produce their DOT track tires in only one compound (the main exceptions being Hoosier and Yokohama). Still, if you want to be quick, there are only a couple possibilities, and you probably already know what they are.

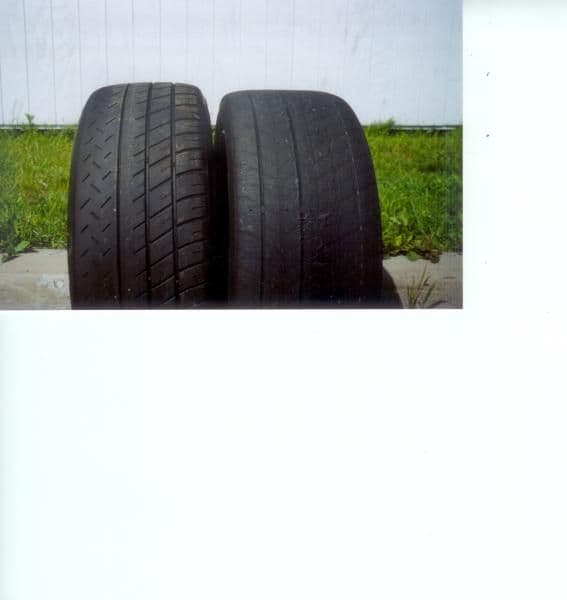

Unfortunately, one can not depend on size markings - they mean almost nothing! Below is an unaltered photograph of two high-end DOT-Approved track tires - a Michelin Pilot Sport Cup, and a Goodyear GS/CS. They are both sitting on the same perfectly flat, level surface, both size 245-45 x 16, both inflated to 27 psi, both mounted on (Porsche) 911 BBS 9 x 16 wheels, both with 35-40 minutes run-in. And, as one might now guess, each Goodyear weighed a couple pounds less than the PSCs. Any predictions about performance potential?

On the track we want our race tires to:

1. Come up to temperature quickly.

2. Stick like glue.

3. Be VERY consistent in grip levels.

4. Give us feedback at all times, and especially before losing adhesion.

5. Provide excellent stick until there is little rubber left.

6. “Grow” the same percentage with temperature increase. (If at the end of a session, our LF is 64⅜” in circumference, then the RF had damn well better be 64⅜” also.)

The need for some of these requirements are a little more subtle. Naturally we want consistency, but feedback is equally critical. Since we are deliberately breaking adhesion virtually everywhere, we need to know constantly what we can “get away with”. The size thing is very important for suspension settings (and aero if you have it.)

Without getting into a technical discussion of slip angles, suffice to say that a race tire delivers its maximum traction when its contact patch is distorted - when the tire is slipping slightly on the pavement. This occurs on hard acceleration, under braking, and during cornering. There are both mechanical and chemical reasons for this “extra grip” phenomenon. What is most important to our discussion here is how to achieve and control those slip angles.

Manufacturers have discovered that a given compound, size, and construction of race tire operates at its best within a certain range of internal temperatures. This is part of each tire’s engineering data, and is typically available to teams using that tire. It is also easily determined on a car-by-car basis through testing, using a stop-watch and a pyrometer - when the stop-watch tells us we are fastest, the pyrometer tells us our optimum (hot) temps.

But what factors affect tire temperatures? Internal “air” pressure, track temperature, car weight and distribution, camber, caster, toe in or out, spring rates, anti-roll bar settings, brake bias, ride height, aero settings, and whether a butterfly flaps its wings . . . . .

And while all of these factors play a part in the tire’s internal temperature, many are outside our control while we are at the track. If you discover a way for an individual team to regulate track temps, by all means let us know - we shall grow rich together! Hopefully, the racecar’s weight distribution and ride height are set independently of tire temps (but not inflation pressures.). If we are running a torsion bar car, or transverse leaf springs, the spring rates are fixed for all intents and purposes. Brake bias is adjusted according to chassis stability under threshold braking, and can not worry much about tire temps. Again, hopefully any problems with caster, camber, or toe settings have shown up in the form of unusual tire wear, or on the pyrometer, and have previously been remedied. Aero adjustments, if available, need to focus on longitudinal centers of pressure and balance. So that leaves us with a very rudimentary, basic method for adjusting a race tire’s temperatures - inflation pressure.

It is best to know a cold, starting inflation pressure, and what that (those) pressure(s) will yield as HOT inflation pressures, for your track tires. For obvious reasons, it is not within the scope of this writing to suggest starting cold, and ultimate hot inflation pressures for each tire, for each size, for each car! One needs to ask racers using similar tire/car configuration, then fine-tune with the pressure gauge and pyrometer.

While racers have always been keenly aware of how critical tire inflation pressure is to handling, the last five-or-so years have seen a renewed interest in getting it exactly right. Central to this topic has been controlling the variation between “cold” and “hot” pressures, and today we discover many club racers are using bottled nitrogen gas in place of compressed air to inflate their tires. Why? Nitrogen is a “dry” gas, containing very little, if any, water vapor. In contrast, compressed air, even with elaborate filters, contains significant water vapor. It is this “added water” which makes for a large variation between the tire’s “cold” inflation pressure, and the “hot”. Minimize the variation in inflation pressure >> minimize fluctuation in internal operating temperatures >> minimize the variation in grip levels.

But isn’t this overkill - a bunch of fuss about nothing? Well, you be the judge: On our Reynard F-2000, a variation of a single pound in inflation pressure equates to changing the SPRING RATE on that corner by 87 POUNDS!

<< CONTINUED ON NEXT POST >>

So, the drivers would become increasingly proficient, but their essentially “street” cars would lag sadly behind. Once they got sick of over-driving their prized Porsche’s potential, they would blindly spend a ton of money, throwing random mods at the car, in the vain hope that it would allow them to go faster. Those who did not pay experienced prep shops to fix their problems would eventually quit out of sheer frustration.

The thought behind our graduated-level seminars was to provide some SIMPLE, ACCURATE guidance to taking a street car, and developing it into a racecar. One of our over-arching criteria was to make the best use of available dollars and time - sort of like a “101 Projects for the Racer”. The end goal was to equip the individual with technically sound methods for evaluating options, and making smart decisions. This may be useful, judging by the never-ending string of threads asking, “What is the best track tire?”; or “ Are 18” wheels better than 17” ?” Next to the motor, wheels and tires are the life-blood of racing!

Where to begin? About four years ago, I was asked to post up a synopsis of our wheel and tire findings (along with other suspension components) on one of the popular Porsche forums. What follows is an abbreviated version of that post. It is quite basic, but should provide a handy spring-board for discussing more advanced aspects in much more detail. So, without further comment . . . . .

I start by making the assertion that there is more to be gained by the proper selection of tires and their wheels, than by ALL of the other suspension components combined.

Also, the comments apply to RACING APPLICATIONS and autocross, focused on racecars, or street cars which are BECOMING racecars.

I include my usual disclaimer about attempting to keep a fairly complex subject AS SIMPLE AS POSSIBLE while covering it thoroughly still applies. To that end, we write in broad concepts, employ metaphors that may not apply in every single case, use plain language, and invoke a minimum of math. (With due apologies in advance to the most experienced racers, other race engineers, and knit-pickers.)

In past posts, we have maintained that “the racecar suspension attempts to manage the chaotic interaction between the race track and the racecar itself - the goal being to keep all 4 tires firmly planted on the track all the time.” So here we start with something as “simple” as tires.

Stating the obvious, there are tires for the street, tires for the track, and then several which attempt to serve “double duty”. Generally speaking, the strictly street tires are not a consideration for the track. The “double duty” tires might be appropriate for the rain if their tread pattern scavenges water effectively. Our focus will be on tires specifically designed for the track.

Following are the primary PHYSICAL characteristics for which we look in a race tire:

1. It has a large footprint (contact patch) for its overall size.

2. Once the release mold has been scrubbed off, the rubber compound is fairly soft to the touch - maybe like a pencil eraser.

3. The sidewall is low-profile and very stiff.

4. Its tread surface which will contact the track is relatively wide.

5. If there are groves in the tread surface, they are few, and very shallow.

6. Light weight.

7. Beads are super-rigid.

8. All tires of the same compound have a common grip level.

The obvious goals here are to get as much sticky rubber in touch with the track as possible, and keep it there. And this leads me to LoPresti’s TireRule #1: If slicks are allowed in your racing class, do not even think about anything else. Your work now becomes determining which manufacture, size, and compound work best with your suspension.

(I have come to realize that NASA employs a conversion factor, or equalization penalty, for using slicks, and here careful testing will be the only way to determine if good slicks can overcome their additional weight assessment.)

A word about COMPOUNDS: The term comes from the notion that the “rubber” in any given tire is made up from a combination of several different “rubber materials” - it is a compound formulation. In racing circles, the term usually refers to how soft or hard the body of the “rubber material”, and how grippy that particular combination. Generally, a soft compound is very sticky, wears fairly quickly, and is designated with a low numerical value. At the other end of the spectrum, a hard compound does not provide as much grip, lasts much longer, and bears a higher numerical value.

If your class limits you to “DOT Approved”, then you have a different range of choices, and the cost-vs-wear factors come into play. Typically, manufacturers produce their DOT track tires in only one compound (the main exceptions being Hoosier and Yokohama). Still, if you want to be quick, there are only a couple possibilities, and you probably already know what they are.

Unfortunately, one can not depend on size markings - they mean almost nothing! Below is an unaltered photograph of two high-end DOT-Approved track tires - a Michelin Pilot Sport Cup, and a Goodyear GS/CS. They are both sitting on the same perfectly flat, level surface, both size 245-45 x 16, both inflated to 27 psi, both mounted on (Porsche) 911 BBS 9 x 16 wheels, both with 35-40 minutes run-in. And, as one might now guess, each Goodyear weighed a couple pounds less than the PSCs. Any predictions about performance potential?

On the track we want our race tires to:

1. Come up to temperature quickly.

2. Stick like glue.

3. Be VERY consistent in grip levels.

4. Give us feedback at all times, and especially before losing adhesion.

5. Provide excellent stick until there is little rubber left.

6. “Grow” the same percentage with temperature increase. (If at the end of a session, our LF is 64⅜” in circumference, then the RF had damn well better be 64⅜” also.)

The need for some of these requirements are a little more subtle. Naturally we want consistency, but feedback is equally critical. Since we are deliberately breaking adhesion virtually everywhere, we need to know constantly what we can “get away with”. The size thing is very important for suspension settings (and aero if you have it.)

Without getting into a technical discussion of slip angles, suffice to say that a race tire delivers its maximum traction when its contact patch is distorted - when the tire is slipping slightly on the pavement. This occurs on hard acceleration, under braking, and during cornering. There are both mechanical and chemical reasons for this “extra grip” phenomenon. What is most important to our discussion here is how to achieve and control those slip angles.

Manufacturers have discovered that a given compound, size, and construction of race tire operates at its best within a certain range of internal temperatures. This is part of each tire’s engineering data, and is typically available to teams using that tire. It is also easily determined on a car-by-car basis through testing, using a stop-watch and a pyrometer - when the stop-watch tells us we are fastest, the pyrometer tells us our optimum (hot) temps.

But what factors affect tire temperatures? Internal “air” pressure, track temperature, car weight and distribution, camber, caster, toe in or out, spring rates, anti-roll bar settings, brake bias, ride height, aero settings, and whether a butterfly flaps its wings . . . . .

And while all of these factors play a part in the tire’s internal temperature, many are outside our control while we are at the track. If you discover a way for an individual team to regulate track temps, by all means let us know - we shall grow rich together! Hopefully, the racecar’s weight distribution and ride height are set independently of tire temps (but not inflation pressures.). If we are running a torsion bar car, or transverse leaf springs, the spring rates are fixed for all intents and purposes. Brake bias is adjusted according to chassis stability under threshold braking, and can not worry much about tire temps. Again, hopefully any problems with caster, camber, or toe settings have shown up in the form of unusual tire wear, or on the pyrometer, and have previously been remedied. Aero adjustments, if available, need to focus on longitudinal centers of pressure and balance. So that leaves us with a very rudimentary, basic method for adjusting a race tire’s temperatures - inflation pressure.

It is best to know a cold, starting inflation pressure, and what that (those) pressure(s) will yield as HOT inflation pressures, for your track tires. For obvious reasons, it is not within the scope of this writing to suggest starting cold, and ultimate hot inflation pressures for each tire, for each size, for each car! One needs to ask racers using similar tire/car configuration, then fine-tune with the pressure gauge and pyrometer.

While racers have always been keenly aware of how critical tire inflation pressure is to handling, the last five-or-so years have seen a renewed interest in getting it exactly right. Central to this topic has been controlling the variation between “cold” and “hot” pressures, and today we discover many club racers are using bottled nitrogen gas in place of compressed air to inflate their tires. Why? Nitrogen is a “dry” gas, containing very little, if any, water vapor. In contrast, compressed air, even with elaborate filters, contains significant water vapor. It is this “added water” which makes for a large variation between the tire’s “cold” inflation pressure, and the “hot”. Minimize the variation in inflation pressure >> minimize fluctuation in internal operating temperatures >> minimize the variation in grip levels.

But isn’t this overkill - a bunch of fuss about nothing? Well, you be the judge: On our Reynard F-2000, a variation of a single pound in inflation pressure equates to changing the SPRING RATE on that corner by 87 POUNDS!

<< CONTINUED ON NEXT POST >>

Last edited by RacePro Engineering; 11-29-2011 at 10:41 PM. Reason: Added photo

#2

Tech Contributor

Thread Starter

<< CONTINUED FROM PREVIOUS POST >>

WHEELS: Again, there are wheels for the street, wheels for the track, and, like tires, several which attempt to serve “double duty”. Street wheels emphasize LOOKS, durability, smooth ride. The time required to mount or dismount is immaterial. Their necessary toughness is usually accomplished through thick, dense material, and equates to heavy weight, which in turn enhances smooth ride qualities.

In contrast, race wheels emphasize strength and lightness, usually accomplished through refined manufacturing processes, more exotic materials, and geometry. Time required to mount and/or dismount can be a huge factor. To show how specialized race wheels can be, BBS focused a tremendous amount of R&D on developing their “limp home” technology, where, in a crash, enough of the wheel remains intact to allow a (slow) return to the pits.

There have been successful “double duty” wheels, and in the Porsche world, the Fuchs and BBS RS-style come immediately to mind. For Corvettes, the older A-Molds are exceptional.

Following are the primary PHYSICAL characteristics for which we look in a race wheel:

1. Strength, against breaking.

2. Light weight.

3. Torsional rigidity, against flexing.

4. Brake ventilation.

5. Aero turbulence.

6. Center-lock, if hubs available.

The most obvious goal here is to allow as much sticky rubber tire to be in touch with the track as possible, and keep it there. Wheels want to be wide - as wide as (1) allowed by your sanctioning body, and (2) will fit under your fenders with the tire mounted. (More recently, certain sanctioning bodies have chosen to limit the TIRE size, as opposed to the traditional wheel size limitation. With this newer complication in mind, we must now add that IF the tire size is specified, the accompanying wheel’s size must be chosen to optimize the grip of that specified tire, as well as the obvious fit-over-the-brakes, fit-under-the-fenders criteria.)

Like everything on a racecar, wheels CAN NOT break, and simultaneously, they need to be lightweight. We shall spend some additional time on this point in a minute. If possible, the bulk of the mass wants to be centered closer to the hub, as opposed to out toward the circumference.

We want lots of feedback from the tire, and very little from the wheel. If the tire’s “tread” is squirming, and the wheel is also flexing, that is hard for the driver to interpret.

We would like the wheel to help ventilate hot air away from the rotors and calipers, AND minimize aerodynamic turbulence around the wheel wells. We probably can not have both, but we keep hoping.

The advantages of center-locks should be self-evident, although we see very few street-cars-that-became-racecars converted.

Owing to their need to be light in weight, race wheels are typically constructed from “extreme” alloys like aluminum or magnesium. They come in two modes of modularity: single piece, and modular.

Single piece wheels offer simplicity and ease of use. Obviously, their offset and backspacing is fixed. They are “good” until they get bent or start cracking, and then they are immediately unusable for the track. They are easy to inspect for flaws. Most are quite rigid.

By far, the most common configuration of modular race wheel is the 3-piece, with a “center” which mounts to the hub, and an inner and an outer rim “half”. The rim “halves” attach to the center section with some sort of gasket and bolt arrangement. These offer some flexibility and economic advantages at the expense of complexity and additional maintenance. One key advantage is that one may experiment with various offsets and backspaces by purchasing a variety of inner and outer “halves”. Another advantage is that if a rim “half” gets bent, the entire wheel may not need to be replaced.

A word about valve stems: There is a story told about World Champion Jackie Stewart. Some years after retirement, he was to drive a few exhibition laps in one of his former Tyrrell Formula One cars. Naturally, many fans and the press were present. In his “walk around” before getting in to drive, he noticed that someone along the chain of ownership had replaced the steel valve stems with the common rubber/plastic which we see on road cars. He asked that the four stems be changed. As luck would have it, no one at the track had these, and they had to be sent for. When they arrived, and the change of the tires was well underway, Stewart noticed that the new ones did not have metallic valve CAPS. In disbelief, he made a further request. At this point, someone in charge challenged him as to how important this really was. His reply was on this nature: I am going to get in and FULLY DRIVE this car! If something as BASIC as metallic valve stems and caps has been overlooked, what else do I need to check?

THE WHEEL / TIRE COMBINATION: There is an on-going dialog revolving around ( pun intended! ) effectiveness of (1) Mounting a slightly narrower tire on a slightly wider wheel, as opposed to (2) picking the widest tire which fits under the fender, and mounting it on the widest wheel allowed by the regs. A common example in using the 9” wide wheel would be a 245-45 tire versus a 275-45. Choice (2) plants more rubber on the track, while choice (1) makes the stance of the sidewalls slightly more leveraged and rigid.

Many racers, especially those saddled with strict class rules regarding gearing, will use a smaller diameter rear wheel/tire combination to achieve more torque, and a “taller” rear wheel/tire combo for greater top speed.

From a racing perspective, the wheel and tire represent a “special case” in two other important areas: Unsprung Weight, and Rotational Mass.

Unsprung weight, as the term implies, is all the mass of the racecar which is not suspended by its springs. For simplicity in figuring, we usually consider ˝ the weight of the springs (or torsion bars), ˝ the weight of the shocks / struts, ˝ the weight of the anti-roll bar assemblies, SOMETIMES part of the half-shafts, all of the spring plates (if any), all of the hubs, all of the brake assemblies, plus all the wheels and tires as UNsprung. Why is this important? This weight can not be “managed” as nicely as normal (sprung) weight. Without getting into the messy physics involved, most racers think of unsprung weight as carrying a heavy “penalty” per pound - usually 3 or 4 times the actual weight. So, if one were to save, say 3 pounds on each tire, 2 pounds on each wheel, and 1 pound on each brake rotor, that would be roughly equivalent to removing 100 pounds of normal weight from the racecar! (Actually, as you will see next, it would be much, MUCH better than that!)

Rotational Mass: The tire/wheel/rotor combination I cited above is an especially bad example, because those three elements represent a “extra special case”. Other than the motor internals and the transaxle, the tire/wheel/rotor assembly is the fastest moving thing on your racecar. Not only is it traveling horizontally at the 143 MPH with you and the rest of the car, but it is ROTATING at the same time, and at a dizzying speed.

So what? Well, things that rotate have their own systems of inertia. When they are motionless, it takes extra force to get them to rotate (accelerate), and once they are rotating, it requires extra force to slow or stop (decelerate), or even turn them in a slightly different direction. Picture the gyroscope. So now, we have not only this incredibly complex geometric structure of a racecar traveling at high speed on its suspension, but we have added 4 little sub-systems, acting somewhat on their own, with their own specialized dynamic problems.

Stay with me now! Without getting into the formulae, the heavier these rotating masses are, the harder it is to accelerate them, and the harder to decelerate, and the harder to alter their direction. Similarly, the larger their diameter, generally the more difficult. Further, the distribution of their mass, away from the center of rotation, has a big effect on this. To get back to our wheel and tire as example, if most of the mass of this assembly were concentrated near the hub (the center of rotation), the entire assembly would be easier to manage. Unfortunately, the typical arrangement is for the high concentration of mass to be around where the tire mounts to the wheel rims - a significant distance from the hub - and requiring considerably more force to manage.

Frankly, most racers do not carry all this detail around in their heads. By deduction, we can sort of encapsulate this tiresome (yes!) Unsprung weight/Rotational mass stuff into a few simple rules:

1..Anything one can do to reduce weight “outboard” of the springs will pay BIG dividends.

2. Anything one can do to reduce the weight of one of these parts that rotate will pay EXTRA BIG dividends.

3. Anything one can do to reduce the diameter of one of these rotating parts will pay BIG dividends. Redistributing the mass closer to the hub will help, too.

4. These performance gains are evident everywhere on the track, and usually cost much less than comparable horsepower gains.

We are aware that some or all of these four points are in contrast to some current trends in the Corvette world, and perhaps sports cars in general. Many manufacturers, to stay in business, follow trends. That not withstanding, these principles have been around since mankind has been racing automobiles. Trends are . . . . . well, you get the idea.

I think we have covered the basics. Again, it is our sincere hope that this information is helpful. And as always, we welcome any questions, comments, and discussion.

Ed LoPresti

WHEELS: Again, there are wheels for the street, wheels for the track, and, like tires, several which attempt to serve “double duty”. Street wheels emphasize LOOKS, durability, smooth ride. The time required to mount or dismount is immaterial. Their necessary toughness is usually accomplished through thick, dense material, and equates to heavy weight, which in turn enhances smooth ride qualities.

In contrast, race wheels emphasize strength and lightness, usually accomplished through refined manufacturing processes, more exotic materials, and geometry. Time required to mount and/or dismount can be a huge factor. To show how specialized race wheels can be, BBS focused a tremendous amount of R&D on developing their “limp home” technology, where, in a crash, enough of the wheel remains intact to allow a (slow) return to the pits.

There have been successful “double duty” wheels, and in the Porsche world, the Fuchs and BBS RS-style come immediately to mind. For Corvettes, the older A-Molds are exceptional.

Following are the primary PHYSICAL characteristics for which we look in a race wheel:

1. Strength, against breaking.

2. Light weight.

3. Torsional rigidity, against flexing.

4. Brake ventilation.

5. Aero turbulence.

6. Center-lock, if hubs available.

The most obvious goal here is to allow as much sticky rubber tire to be in touch with the track as possible, and keep it there. Wheels want to be wide - as wide as (1) allowed by your sanctioning body, and (2) will fit under your fenders with the tire mounted. (More recently, certain sanctioning bodies have chosen to limit the TIRE size, as opposed to the traditional wheel size limitation. With this newer complication in mind, we must now add that IF the tire size is specified, the accompanying wheel’s size must be chosen to optimize the grip of that specified tire, as well as the obvious fit-over-the-brakes, fit-under-the-fenders criteria.)

Like everything on a racecar, wheels CAN NOT break, and simultaneously, they need to be lightweight. We shall spend some additional time on this point in a minute. If possible, the bulk of the mass wants to be centered closer to the hub, as opposed to out toward the circumference.

We want lots of feedback from the tire, and very little from the wheel. If the tire’s “tread” is squirming, and the wheel is also flexing, that is hard for the driver to interpret.

We would like the wheel to help ventilate hot air away from the rotors and calipers, AND minimize aerodynamic turbulence around the wheel wells. We probably can not have both, but we keep hoping.

The advantages of center-locks should be self-evident, although we see very few street-cars-that-became-racecars converted.

Owing to their need to be light in weight, race wheels are typically constructed from “extreme” alloys like aluminum or magnesium. They come in two modes of modularity: single piece, and modular.

Single piece wheels offer simplicity and ease of use. Obviously, their offset and backspacing is fixed. They are “good” until they get bent or start cracking, and then they are immediately unusable for the track. They are easy to inspect for flaws. Most are quite rigid.

By far, the most common configuration of modular race wheel is the 3-piece, with a “center” which mounts to the hub, and an inner and an outer rim “half”. The rim “halves” attach to the center section with some sort of gasket and bolt arrangement. These offer some flexibility and economic advantages at the expense of complexity and additional maintenance. One key advantage is that one may experiment with various offsets and backspaces by purchasing a variety of inner and outer “halves”. Another advantage is that if a rim “half” gets bent, the entire wheel may not need to be replaced.

A word about valve stems: There is a story told about World Champion Jackie Stewart. Some years after retirement, he was to drive a few exhibition laps in one of his former Tyrrell Formula One cars. Naturally, many fans and the press were present. In his “walk around” before getting in to drive, he noticed that someone along the chain of ownership had replaced the steel valve stems with the common rubber/plastic which we see on road cars. He asked that the four stems be changed. As luck would have it, no one at the track had these, and they had to be sent for. When they arrived, and the change of the tires was well underway, Stewart noticed that the new ones did not have metallic valve CAPS. In disbelief, he made a further request. At this point, someone in charge challenged him as to how important this really was. His reply was on this nature: I am going to get in and FULLY DRIVE this car! If something as BASIC as metallic valve stems and caps has been overlooked, what else do I need to check?

THE WHEEL / TIRE COMBINATION: There is an on-going dialog revolving around ( pun intended! ) effectiveness of (1) Mounting a slightly narrower tire on a slightly wider wheel, as opposed to (2) picking the widest tire which fits under the fender, and mounting it on the widest wheel allowed by the regs. A common example in using the 9” wide wheel would be a 245-45 tire versus a 275-45. Choice (2) plants more rubber on the track, while choice (1) makes the stance of the sidewalls slightly more leveraged and rigid.

Many racers, especially those saddled with strict class rules regarding gearing, will use a smaller diameter rear wheel/tire combination to achieve more torque, and a “taller” rear wheel/tire combo for greater top speed.

From a racing perspective, the wheel and tire represent a “special case” in two other important areas: Unsprung Weight, and Rotational Mass.

Unsprung weight, as the term implies, is all the mass of the racecar which is not suspended by its springs. For simplicity in figuring, we usually consider ˝ the weight of the springs (or torsion bars), ˝ the weight of the shocks / struts, ˝ the weight of the anti-roll bar assemblies, SOMETIMES part of the half-shafts, all of the spring plates (if any), all of the hubs, all of the brake assemblies, plus all the wheels and tires as UNsprung. Why is this important? This weight can not be “managed” as nicely as normal (sprung) weight. Without getting into the messy physics involved, most racers think of unsprung weight as carrying a heavy “penalty” per pound - usually 3 or 4 times the actual weight. So, if one were to save, say 3 pounds on each tire, 2 pounds on each wheel, and 1 pound on each brake rotor, that would be roughly equivalent to removing 100 pounds of normal weight from the racecar! (Actually, as you will see next, it would be much, MUCH better than that!)

Rotational Mass: The tire/wheel/rotor combination I cited above is an especially bad example, because those three elements represent a “extra special case”. Other than the motor internals and the transaxle, the tire/wheel/rotor assembly is the fastest moving thing on your racecar. Not only is it traveling horizontally at the 143 MPH with you and the rest of the car, but it is ROTATING at the same time, and at a dizzying speed.

So what? Well, things that rotate have their own systems of inertia. When they are motionless, it takes extra force to get them to rotate (accelerate), and once they are rotating, it requires extra force to slow or stop (decelerate), or even turn them in a slightly different direction. Picture the gyroscope. So now, we have not only this incredibly complex geometric structure of a racecar traveling at high speed on its suspension, but we have added 4 little sub-systems, acting somewhat on their own, with their own specialized dynamic problems.

Stay with me now! Without getting into the formulae, the heavier these rotating masses are, the harder it is to accelerate them, and the harder to decelerate, and the harder to alter their direction. Similarly, the larger their diameter, generally the more difficult. Further, the distribution of their mass, away from the center of rotation, has a big effect on this. To get back to our wheel and tire as example, if most of the mass of this assembly were concentrated near the hub (the center of rotation), the entire assembly would be easier to manage. Unfortunately, the typical arrangement is for the high concentration of mass to be around where the tire mounts to the wheel rims - a significant distance from the hub - and requiring considerably more force to manage.

Frankly, most racers do not carry all this detail around in their heads. By deduction, we can sort of encapsulate this tiresome (yes!) Unsprung weight/Rotational mass stuff into a few simple rules:

1..Anything one can do to reduce weight “outboard” of the springs will pay BIG dividends.

2. Anything one can do to reduce the weight of one of these parts that rotate will pay EXTRA BIG dividends.

3. Anything one can do to reduce the diameter of one of these rotating parts will pay BIG dividends. Redistributing the mass closer to the hub will help, too.

4. These performance gains are evident everywhere on the track, and usually cost much less than comparable horsepower gains.

We are aware that some or all of these four points are in contrast to some current trends in the Corvette world, and perhaps sports cars in general. Many manufacturers, to stay in business, follow trends. That not withstanding, these principles have been around since mankind has been racing automobiles. Trends are . . . . . well, you get the idea.

I think we have covered the basics. Again, it is our sincere hope that this information is helpful. And as always, we welcome any questions, comments, and discussion.

Ed LoPresti

Last edited by RacePro Engineering; 11-29-2011 at 10:16 PM.

#3

Race Director

Thanks Ed,

It's great to have all that info in one place. First question I have regards this part:

THE WHEEL / TIRE COMBINATION: There is an on-going dialog revolving around ( pun intended! ) effectiveness of (1) Mounting a slightly narrower tire on a slightly wider wheel, as opposed to (2) picking the widest tire which fits under the fender, and mounting it on the widest wheel allowed by the regs. A common example in using the 9” wide wheel would be a 245-45 tire versus a 275-45. Choice (2) plants more rubber on the track, while choice (1) makes the stance of the sidewalls slightly more leveraged and rigid.

If you have a choice either in your rules, or if you don't need to built to any particular specification, would a wider tire on a wider rim (to still have an optimum leveraged & rigid sidewall) be the obvious choice? Or could you eventually have "too much tire" that affects turn in (especially slaloms - specific to autox type events).

It's great to have all that info in one place. First question I have regards this part:

THE WHEEL / TIRE COMBINATION: There is an on-going dialog revolving around ( pun intended! ) effectiveness of (1) Mounting a slightly narrower tire on a slightly wider wheel, as opposed to (2) picking the widest tire which fits under the fender, and mounting it on the widest wheel allowed by the regs. A common example in using the 9” wide wheel would be a 245-45 tire versus a 275-45. Choice (2) plants more rubber on the track, while choice (1) makes the stance of the sidewalls slightly more leveraged and rigid.

If you have a choice either in your rules, or if you don't need to built to any particular specification, would a wider tire on a wider rim (to still have an optimum leveraged & rigid sidewall) be the obvious choice? Or could you eventually have "too much tire" that affects turn in (especially slaloms - specific to autox type events).

Last edited by froggy47; 11-30-2011 at 01:10 AM.

#4

Tech Contributor

Member Since: Oct 1999

Location: Charlotte, NC (formerly Endicott, NY)

Posts: 40,076

Received 8,911 Likes

on

5,325 Posts

Ed,

Great start.

Bill

Great start.

Bill

#7

Tech Contributor

Thread Starter

Gentlemen,

Thank you for the kind words! I recognize this a lot of rudimentary info to wade through, and I truly appreciate your time and opinions - especially from the illustrious group who has responded.

Hopefully, we can branch off into various, more advanced discussions, as the one in which Bob is already taking us.

Ed

Thank you for the kind words! I recognize this a lot of rudimentary info to wade through, and I truly appreciate your time and opinions - especially from the illustrious group who has responded.

Hopefully, we can branch off into various, more advanced discussions, as the one in which Bob is already taking us.

Ed

#10

Tech Contributor

Thread Starter

If you have a choice either in your rules, or if you don't need to built to any particular specification, would a wider tire on a wider rim (to still have an optimum leveraged & rigid sidewall) be the obvious choice? Or could you eventually have "too much tire" that affects turn in (especially slaloms - specific to autox type events).

In so many ways, the autocross (and maybe particularly a slalom) represents a "special case", because of the ultra-short time allowed to warm, and get a scrub going on the tires.

Years ago, we autocrossed a formula car, and used Goodyear 120 compound slicks (back when they made them that soft) - 7" and 9" widths. To answer your question, I am attempting to picture what that would have been like with EXCESSIVELY wide wheels/tires.

The car was under 960 pounds without driver, but I am absolutely certain that we could have made effective use of Formula Atlantic sizes - 10" and 14" if they were allowed. (Maybe 150% increase?) I believe that wider than that may have presented 2 real problems: getting the tires up to temperature, and having the car "too wide" to get through a slalom quickly. I do firmly believe that the trade-offs of additional unsprung weight, and rotational mass, would have been worth it.

On the big tracks, however, when one has lots of opportunity to scrub those tires, I can not think of a single instance where I could not have used more grip!

Ed

Last edited by RacePro Engineering; 12-02-2011 at 02:23 PM.

#11

Tech Contributor

Thread Starter

Thanks Mike and Everette.

Most of it is stuff we, on this Forum, all know. All I have tried to do is sort of systemetize the bits and pieces. I appreciate the input.

Ed

Most of it is stuff we, on this Forum, all know. All I have tried to do is sort of systemetize the bits and pieces. I appreciate the input.

Ed

#13

Race Director

Bob,

In so many ways, the autocross (and maybe particularly a slalom) represents a "special case", because of the ultra-short time allowed to warm, and get a scrub going on the tires.

Years ago, we autocrossed a formula car, and used Goodyear 120 coupound slicks (back when they made them that soft) - 7" and 9" widths. To answer your question, I am attempting to picture what that would have been like with EXCESSIVELY wide wheels/tires.

The car was under 960 pounds without driver, but I am absolutely certain that we could have made effective use of Formula Atlantic sizes - 10" and 14" if they were allowed. (Maybe 150% increase?) I believe that wider than that may have presented 2 real problems: getting the tires up to temperature, and having the car "too wide" to get through a slalom quickly. I do firmly believe that the trade-offs of additional unsprung weight, and rotational mass, would have been worth it.

On the big tracks, however, when one has lots of opportunity to scrub those tires, I can not think of a single instance where I could not have used more grip!

Ed

In so many ways, the autocross (and maybe particularly a slalom) represents a "special case", because of the ultra-short time allowed to warm, and get a scrub going on the tires.

Years ago, we autocrossed a formula car, and used Goodyear 120 coupound slicks (back when they made them that soft) - 7" and 9" widths. To answer your question, I am attempting to picture what that would have been like with EXCESSIVELY wide wheels/tires.

The car was under 960 pounds without driver, but I am absolutely certain that we could have made effective use of Formula Atlantic sizes - 10" and 14" if they were allowed. (Maybe 150% increase?) I believe that wider than that may have presented 2 real problems: getting the tires up to temperature, and having the car "too wide" to get through a slalom quickly. I do firmly believe that the trade-offs of additional unsprung weight, and rotational mass, would have been worth it.

On the big tracks, however, when one has lots of opportunity to scrub those tires, I can not think of a single instance where I could not have used more grip!

Ed

Here is a slo mo launch that I picked because it shows the wheel/tire combo a bit. Jeff's Sprite is all over the net. 7 or 8 time National's & 3 Pro Solo Champ. He has given me some good setup tips. Car is about #1800 with 360+ at the wheels. Rotary/turbo engine. Probably one of the top 5 slalom cars in the country (not counting shifter karts)

We use the softest tires (usually a6) possible because there is NO warmup lap. Your 1st lap of the day counts for score, 2 or 3 more and you are done.

I think your point on the width of the car (including wheels) is key. On a slalom where the cones are close spaced my width with the widest combo could be a detriment, on a longer spaced(faster) slalom I would wish for the wider wheel tire combo.

We pace off the slalom to discover "course design tricks" such as where the spacing is not equal on all the cones.

Thanks for your insight on that, makes sense.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bx8FW...layer_embedded

Last edited by froggy47; 12-01-2011 at 12:08 AM.

#14

Tech Contributor

Thread Starter

My pleasure, David. I am glad it is useful info.

---------------------------------------

Bob,

Thanks for posting that link to the Sprite modified. The slow motion certainly highlights the quest for grip, and one highly successful solution.

Watching it repeatedly, it also points out an additional aspect of the autocross being a “special case” for car preparation. Jeff and his car are obviously dominant, as their record shows. However, one can easily predict that the same car would not do well on a road course, even with proper gearing and removal of that massive rear airfoil. And this brings us to a topic I only brushed upon above -- TURBULENCE. Rotating tires create a lot of it!

Fortunately for us ‘Vette racers, our fenders do a fair (pun intended) job of keeping quite wide tires out of the air stream. And the OEM spoilers, and the fact that we are low to the ground, contribute to the aero efficiency. However, when one starts sticking tires outside those fenders, one is inviting 3 different types of drag. We get increased form drag, simply because our car is now “wider”. We suffer massive interruption of laminar air flow on the sides of the rear, just where we want the air to leave the body smoothly. And the chaotic turbulence on the top surfaces of those tires actually generates lift. In summation, it becomes real messy!

Ed

---------------------------------------

Bob,

Thanks for posting that link to the Sprite modified. The slow motion certainly highlights the quest for grip, and one highly successful solution.

Watching it repeatedly, it also points out an additional aspect of the autocross being a “special case” for car preparation. Jeff and his car are obviously dominant, as their record shows. However, one can easily predict that the same car would not do well on a road course, even with proper gearing and removal of that massive rear airfoil. And this brings us to a topic I only brushed upon above -- TURBULENCE. Rotating tires create a lot of it!

Fortunately for us ‘Vette racers, our fenders do a fair (pun intended) job of keeping quite wide tires out of the air stream. And the OEM spoilers, and the fact that we are low to the ground, contribute to the aero efficiency. However, when one starts sticking tires outside those fenders, one is inviting 3 different types of drag. We get increased form drag, simply because our car is now “wider”. We suffer massive interruption of laminar air flow on the sides of the rear, just where we want the air to leave the body smoothly. And the chaotic turbulence on the top surfaces of those tires actually generates lift. In summation, it becomes real messy!

Ed

#16

Thanks for the lesson! I Look forward to your next installment.

What comments can you make about getting tires hot enough to have meaningful pryrometer readings? It is possible to "think" one is driving hard enough and come in the hot pits getting "even" pyrometer readings and "assume" one is going in the right direction. In other words do you have any comments on how to achieve meaningful pyrometer readings?

What comments can you make about getting tires hot enough to have meaningful pryrometer readings? It is possible to "think" one is driving hard enough and come in the hot pits getting "even" pyrometer readings and "assume" one is going in the right direction. In other words do you have any comments on how to achieve meaningful pyrometer readings?

#17

Tech Contributor

Thread Starter

Something magic happens when the driver starts to turn consistent laps - all within around one second of each other (adjusted for traffic). Prior to that time, it is very difficult to evaluate changes of any type, be they tire compounds, or aero adjustments, or suspension settings. But once that "baseline" is established, now one has something concrete against which to compare.

So while a pyrometer can be used at any time to uncover glaring problems with alignment, the instrument really comes into its own once consistent laps are being laid down.

As a point of interest, Van Diemen Corporation provides a software package with their ZTec-based F-2000 racecars, that is designed to "advise" the team on complete chassis and suspension setup, based SOLELY upon pyrometer readings.

[1] The car comes into the hot pits

[2] Standard pyrometer readings are taken instantly

[3] The readings are typed into, or downloaded into, the software program

[4] The laptop responds, "Reduce rear antiroll stiffness to setting #3. Increase rebound reisitance on the front dampers by two clicks. Increase rear wing main plane angle of incidence by 1 degree."

Really facinating.

Ed

#18

Le Mans Master

Something magic happens when the driver starts to turn consistent laps - all within around one second of each other (adjusted for traffic). Prior to that time, it is very difficult to evaluate changes of any type, be they tire compounds, or aero adjustments, or suspension settings. But once that "baseline" is established, now one has something concrete against which to compare.

So, I'll ask my question pertaining to autocross: Other than "lap" times, what can we use to measure the "goodness" of our alignments, tire sizes, etc?

Thanks again, and have a good one,

Mike

#19

Tech Contributor

Thread Starter

Mike,

I am sort of hoping that one of our other dyed-in-the-wool autocrossers (Solofast? Froggy?) chimes in here with some additional suggestions. Meanwhile, I can offer the advice of seat-of-the-pants tuning, and "reading" your tires. (And you are probably already doing this to some degree.)

The obvious "goodness" in the suspension setup will be dialed in with the SOP method. Is the car generally oversteering? Is braking stable? Can I get transitions smoothly? What will allow me to put the power down earlier? These are all handled with suspension tweaks, and we could devote several other threads discussing each.

ALONG WITH suspension adjustments, we need to ensure that we are getting everything possible out of our tires. Frequently, the less-than-a-full-minute autocross run does not heat the tires sufficiently to gain any meaningful pyrometer readings - it is simply too brief a time, no matter how hard one is driving. But what it does do is "scrub" those tires.

As soon as one completes a run, and BEFORE driving through the dust, dirt, and debris in the paddock, closely INSPECT each of the tires. Around the circumfrence of the tire, on the "tread", the rubber will be worn, black, and hopefully hot - this is the scrub. Now looking across the surface of the tire's tread, determine how much of that tread is being used. If the scrub spans the tread completely, using the surface from one shoulder to the other, and maybe SLIGHTLY onto the sidewalls (for you radial tire users), then that tire is being used to its fullest.

A scrub that does not extend to the edges of BOTH shoulders typically indicates too high inflation pressure, A scrub that is visably darker on BOTH shoulders than in the center typically indicates under-inflation. A scrub that reaches the outside, but not the inside shoulder typically indicates too little negative camber, OR too much toe IN. A scrub that reaches the inside, but not the outside shoulder typically indicates too much negative camber, OR too much toe OUT.

Nothing, but nothing, beats practice and testing on a closed circut. When that is not available, one uses what is available.

Hope this helps,

Ed

I am sort of hoping that one of our other dyed-in-the-wool autocrossers (Solofast? Froggy?) chimes in here with some additional suggestions. Meanwhile, I can offer the advice of seat-of-the-pants tuning, and "reading" your tires. (And you are probably already doing this to some degree.)

The obvious "goodness" in the suspension setup will be dialed in with the SOP method. Is the car generally oversteering? Is braking stable? Can I get transitions smoothly? What will allow me to put the power down earlier? These are all handled with suspension tweaks, and we could devote several other threads discussing each.

ALONG WITH suspension adjustments, we need to ensure that we are getting everything possible out of our tires. Frequently, the less-than-a-full-minute autocross run does not heat the tires sufficiently to gain any meaningful pyrometer readings - it is simply too brief a time, no matter how hard one is driving. But what it does do is "scrub" those tires.

As soon as one completes a run, and BEFORE driving through the dust, dirt, and debris in the paddock, closely INSPECT each of the tires. Around the circumfrence of the tire, on the "tread", the rubber will be worn, black, and hopefully hot - this is the scrub. Now looking across the surface of the tire's tread, determine how much of that tread is being used. If the scrub spans the tread completely, using the surface from one shoulder to the other, and maybe SLIGHTLY onto the sidewalls (for you radial tire users), then that tire is being used to its fullest.

A scrub that does not extend to the edges of BOTH shoulders typically indicates too high inflation pressure, A scrub that is visably darker on BOTH shoulders than in the center typically indicates under-inflation. A scrub that reaches the outside, but not the inside shoulder typically indicates too little negative camber, OR too much toe IN. A scrub that reaches the inside, but not the outside shoulder typically indicates too much negative camber, OR too much toe OUT.

Nothing, but nothing, beats practice and testing on a closed circut. When that is not available, one uses what is available.

Hope this helps,

Ed

#20

Tech Contributor

Thread Starter

Mike, I did not address your question about tire size.

While some will argue that "too much tire" does not rise to temperature quickly enough for an autocross, I believe the trade-offs of having the shortest diameter, largest footprint one can get, and then driving the car for all it is worth, trumps a narrower tire. (And I am pleased to hear disputing arguments, so feel free . . . . )

Ed

Ed