C6 C7 Corvette: How to Break In Your Engine

It is oh-so-tempting, but if you want to enjoy your new Corvette for a long time, you have to take it easy for a while at first.

This article applies to the Corvette C6 (2005-2013) and C7 (2014-2015).

The papers are all signed, the big check has been handed over, and you're finally ensconced in your brand-new Corvette. You fire it up—and it sounds nice. You slip it into gear and hit the throttle, tearing away from the dealership in a roar of exhaust and a cloud of tire smoke. Exciting and very satisfying, but you may live to regret it. Just like a new baseball glove, your Corvette needs to be broken in properly—and not just the engine—before it's ready for a real game.

Read and follow what it says in the owner's manual

Even before you start your new Corvette, take a few minutes to browse the manual—especially the section entitled "New Vehicle Break-In."

For the first 500 miles, avoid full throttle starts and abrupt stops and keep it under 4,000 rpm—that means also avoiding downshifts that would put the RPMs over 4,000 (In fact, your C7 Corvette will tell you when it's okay to rev it up—see Figure 1 and Figure 2). Avoid driving at a constant speed for more than a few minutes—if you're on the highway, do a few miles at 55, a few at 65, a few at 60 and so on. Don't lug or let the engine labor in high gear at low speeds—ever—even after the break-in period. Until you've passed the 1,500-mile mark, don't use your car in any kind of track or autocross stuff. Also, be aware that oil and fuel consumption may be higher than normal during the first 1,500 miles—check the oil every time you fill up with gas for the first 1,500-2,000 miles.

Figure 1. The caution line is at 3,500 RPM up to 499 miles.

Figure 2. Like magic, at 500 miles, you're good to go to 6,500 RPM.

Featured Video: C7 Corvette Stingray Breaking-In

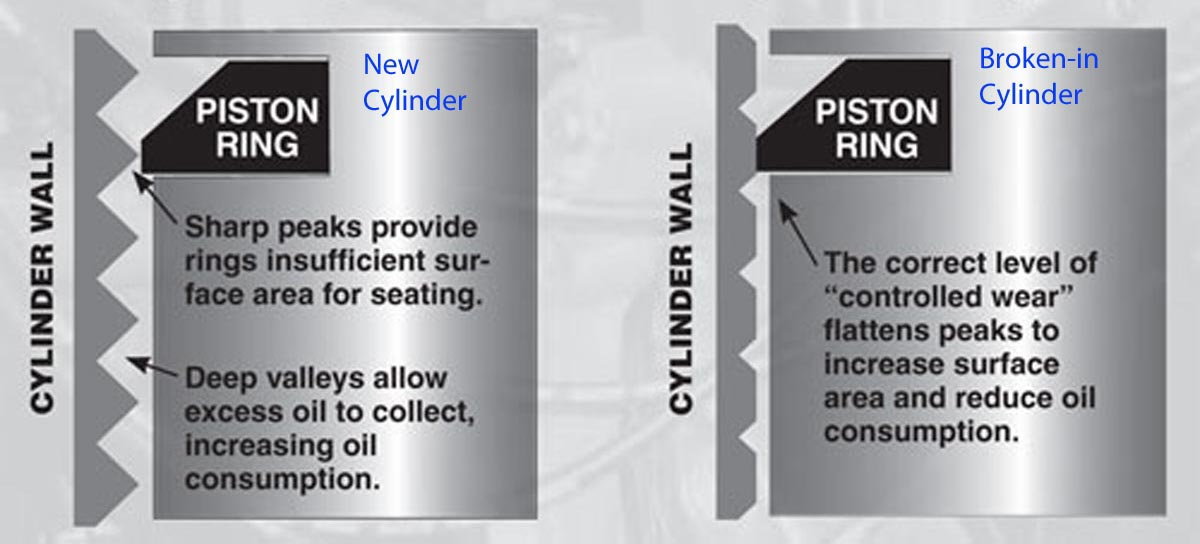

General Motors does not describe the steps to breaking in your new Corvette just for fun. The engine is a work of automotive engineering art, and it's made up of a lot of parts that move up, down, and around in close quarters with nothing between them but a very thin film of oil. All of these parts are machined or forged according to what are called "manufacturing tolerances"—basically, a margin for error. Not much margin, but these engine parts will inevitably have microscopic high and low spots on their surfaces. In the cylinders, for example, this helps to explain why oil consumption can be higher-than-usual during the break-in period (Figure 4).

The same is true for transmission gears and others. It takes some wear under load for those little, high spots to get worn nice and smooth so they fit just right. Run the engine too hard before this happens, and one or more of those high spots might rub through the thin film of oil, resulting in metal-to-metal contact. That generates a lot of heat; things get warped and, well, that's not the sort of thing that leads to an engine leading a long and healthy life.

Go easy on the tires for the first 200 miles or so

In fact, many tire manufacturers recommend a 500-mile break-in period for new tires, so resist the temptation to do "just one" big burn-out, or see how fast you can take that sweeping on-ramp curve. When tires are being made, they're coated with a special lubricant so they don't stick to the mold when they're finished cooking. It takes a while for this lubricant to wear off, and until it does, the tires won't give you the kind of grip you'd expect from a high-performance tire. As well, if you floor it or hammer on the brakes, those same lubricants can cause the tire to slip on the rim, affecting balance.

Break in the brakes, too

The same applies to the brakes on your new Vette, and again, many manufacturers recommend a break-in period of up to 500 miles. Be especially careful for the first few stops—pads and rotors may still have residue from the manufacturing process on them, and they may not give the stopping power you're expecting. After that, avoid hard braking for at least the first 200 miles. By allowing the heat experienced by the pads and rotors to build up gradually, you're giving the pads a chance to put a consistent layer of what's called "transfer film" onto the rotors: the key to smooth, effective braking performance over the long term.

Related Discussions

- How to Break In the C6 Corvette - Corvetteforum.com

- What's the C7’s Break-In Process? - Corvetteforum.com